Background

It is generally accepted that the musical modes can be traced back to different tribes in ancient Greek society, which dates their origins to the very broad range of 800BC to 600AD, give or take a couple of hundred years! Legend has it that each of the communities (The Ionians, The Dorians, The Phrygians, etc) loved their music and had their own distinctive ‘feel’ based on the unique scales (modes) that they favoured.

Today, musical scholars tell us that the modern Lydian mode actually differs from the original one used by the ancient Greeks, based on the scant supporting documentation. Yes, I know, in 2016, it’s hard to imagine a world without electronics, let alone the internet, phones, social media and communication mediums, (good or bad!) In fact, just for the sake of trivia, the first recording device was invented by Thomas Edison in 1877.

Anyway, the experts tell us that the original modes were used as monophonic melodic lines, so their context is very different from today – the modern modes get their unique flavour from the way they fit in with the underlying chord progressions.

Regardless, the modern modes are all about the sound, the feel, the flavour – and not about the historical significance or the theory. It is the emotion that is stirred by a particular piece of music.

Contributed by Mark Smith for the Roland Australia Blog

The Lydian Flavour

As you will see in the theory section below, the Lydian mode is suited to wide, open-sounding chords, like a major 7th and its extensions. When played over these types of chords, the Lydian mode has a light, airy feel to it. Think floating, or the kind of music you’d hear when travelling through space. For this reason most Lydian based songs are performed at a slower tempo.

I guess you could call it the ‘airhead’ mode, sort of light and vague, but at the same time happy and content with a slower pace – maybe this was how the ancient Lydian musicians lived their lives.

There are loads of Lydian flavoured songs by Steve Vai, Eric Johnson, Rush, Dream Theater and many more, but probably the best example comes from guitar maestro Joe Satriani. In this video, Satriani talks about how he used the Lydian modal structure when he wrote ‘Flying in a Blue Dream’. It is great to hear him not only explain how he approached the melody, but also the underlying chord structure.

Personally, I love the ‘Flying in a Blue Dream’ song title, as it sums up the emotion of the Lydian mode perfectly. As always, there are sections of the song that deviate from the Lydian modal structure, but this is exactly how to use modes – in the context of distinctive underlying chord progressions, looking for patterns. It is rare that someone will use just one mode for an entire song.

The Theory

In the first ‘Introduction to Modes’ article, we saw how the Lydian mode is the 4th mode of the relative major scale (starts and ends on the fourth note of a key).

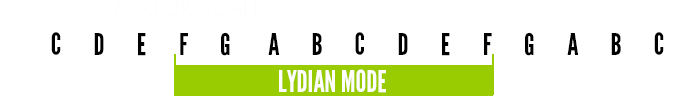

For example, if we are in the key of C, the notes of the major scale would be C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C. The Lydian mode contains exactly the same notes, but starts and ends on the 4th note, so it would be F, G, A, B, C, D, E, F and look like this:

Since the F Lydian mode contains exactly the same notes of the C major scale, why bother with a fancy name? Good question! Because the sound of the mode depends on the underlying chords. Why? Well, first you need to understand how the Lydian mode compares to its relative major scale.

F Major scale F, G, A, Bb, C, D, E, F

F Lydian mode F, G, A, B, C, D, E, F

You can see from the diagram above that the difference between the F Major scale and F Lydian is that the fourth tone has been raised a semitone (Bb to B).

For this reason, the Lydian mode is often written as 1 2 3 #4 5 6 7 and it is this raised 4th tone that gives the Lydian mode its unique identity.

When we are in the key of C, the F Lydian mode contains the notes F G A B C D E F so by using basic chord theory, if we take the 1st, 3rd, 5th, and 7th notes (F A C E), we have an FMaj7 chord.

Can You Explain That In Plain English??

Let’s look at it another way. When you are building chords from the major scale, if you use the 4th note of a scale, it will clash with the 3rd note. This is why chords like sus4 don’t include the 3rd scale degree. That is, most chords either have the 3rd or the 4th – but not both.

The Lydian mode addresses this very issue, and with its raised 4th it changes the clashing, dissonant sound to something new that is cool and spacious. However, this new raised 4th note can now clash with the 5th note of a chord, so some soloists prefer if the accompanying musicians play chords that omit the 5th.

This creates a lot of space, suiting the Lydian flavour and letting the soloist highlight the raised 4th. In cases where the 5th tone in the chord has been left out, it is best to include some extensions, which with the right voicing, give the chords a really wide, spacious feel that is just calling out for Lydian solos over the top.

When to Use the Lydian Mode

Typically, a guitarist would do little more than simply work out the overall key of the song before starting to solo. However, using modes requires that you think a little differently – break down the song into sections (verse, chorus, middle, etc.), take a look at the chord structure for each section and then choose a mode.

If you find all that theory a bit confusing, don’t fret (bad pun intended), all you need to remember is that the Lydian mode would go well over the major chord extensions, e.g. Maj7, Maj9, Maj7#11, Maj9#11, etc.

Sometimes it is easier to just let your ears be the guide and your fingers play the fret positions as indicated. You will hear it when the mode is used in the right context.

Cue the music and thank Roberto Restuccia for creating a backing track and putting together a short video example that shows the Lydian mode in all its glory.

Video Example

In the video below, guitarist Roberto Restuccia demonstrates the light and airy, spacious feel of the Lydian mode. This time around he has played it straight down the line for the first 35 seconds, so you can get a great indication of how the Lydian mode sounds in context. After this, in the second half of the video Roberto solos in the Phrygian mode (over different chords), so you can get a side by side comparison of the modes.

Try it Out for Yourself

Now that you know the history and the theory, here comes the fun part – download everything you need for free, then try it out for yourself. After a couple of practice runs, you’ll probably be an expert, so feel free to express your opinion on exactly what constituted the ‘original’ Lydian mode and what emotions it evoked.

DOWNLOAD► C Lydian Mode Positions

Related Articles

Ionian Mode

Dorian Mode

Aeolian Mode

Locrian Mode

Mixolydian Mode

Phrygian Mode